Below are some of the photographs taken by participants in the project, with accompanying stories about what the photographs represent in terms of their experiences of sexuality and disability:

BADIEN’S STORY

“Most of the time people don’t understand people with physical disabilities. For example, for me going about on my routes on my way home, this is the only route that I can take to get off the main section of the main road. But for me going through there I have to go through stones and I have to go through sand. There are even potholes that sink in the sand. And most of the time as well, if I have to go through that section there, there are always cars parked on that side there. This is a workshop and, if I have to pass there, there’s always a person who would utter these words: “why are you on my property?” So I have no choice but to turn around and take the freeway. And what happened to me there also a few months ago, a taxi driver knocked me on my elbow and I fell from my chair. So I’m very sceptic about taking that route. There you can see, here’s the car in the driveway and there’s the door for you to enter. That small space there, they are always busy with mechanical things there, but I have to wait for them and ask permission because it’s very, very up-and-down there where they are busy. That is why the owner of that place always complains about going up there. But now, since I’ve told him about this project, if he’s busy there, he will tell his guys to stop and make way for me to go through. So that is what the understanding is.” (Badien)

BONGANI’S STORY

“This is a church. Well, for me, I just thought it represents a lot in terms of tradition, institution and values. For instance, it almost inspires a family sort of orientated way of engaging with spirituality. So when I thought about it, you know, just thinking about it perhaps as a boy growing up and that at some point I’m going to have a wife and children, and to be able to fit into that sort of structure. So it just made me think about my own family and my parents’ divorce. I always looked up to my father and I value him for who he is and what he always represented. But when they divorced, everything that I was thinking that I’m bound to aspire to, it was all falling apart right in front of my very eyes. So I’m thinking to myself, okay, if my father, who is this role model and epitome of possibility has failed at that and was unable to make it work and make it last and all those good things, what chance do I have as a male with a disability? Because I’m thinking, you know, he’s in a better position to make it work. Surely he’s got more tools and more capability to make it successful. So for me, after that event, for instance, I just became a sceptic. Do I just abandon the whole concept about getting into relationships? Do I remain reliant and rooted in the so-called values of family tradition?” (Bongani)

FATIMA’S STORY

“So I was told that your hair is your beauty and, if you die, it covers you. So I’m trying to illustrate the importance for me of wearing a scarf and being dressed in a certain way. But other than that, that’s all that I’m holding onto, it’s my beautiful long hair. It still makes me feel that I’m a woman.” (Fatima)

CLEONE’S STORY

“I can’t hide my flaws and imperfections like other people can. Mine is there for the world to see. In the process of rediscovering my sexuality, I have learned to use what I have to seduce and entice. The silent battles I have fought of self-acceptance and validation has left me with the realisation that I no longer have to hide the naked beautiful truth of who I am…a woman in every essence of the word.” (Cleone)

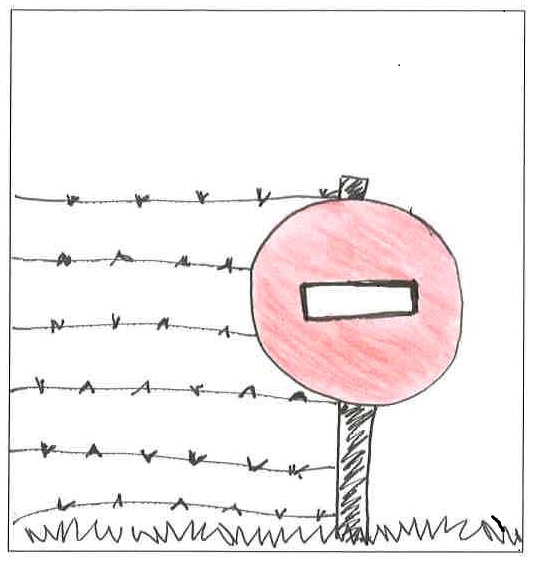

MARTHA’S STORY

“The no-entry sign. I come from a conservative background, a conservative Christian background, so for me, as I was growing up, the whole thing of sexuality and even marrying was very closely tied to having children. And everybody just took for granted, because I couldn’t have children, I wouldn’t marry. So that’s something I rebelled against and struggled with. But at the same time, what it also did, it made me sort of…a few times that I started in friendships with boys or with young men, I would sort of put up the blockades earlier so that I wouldn’t get to that point. And ja, it was painful and I was angry a lot of the time. But this epitomises it, that yes, there is a way, and a lot of my friends…I mean, when I was in my twenties quite a few of them had been married and unfortunately marriages were breaking up, so I knew that marriage as such wasn’t an easy road, but for me it was this no-entry. You know, that was the message that I was getting. I mean, I always hoped. Even through all the time that I knew about the no entry sign, there was hope, but it was something that I wasn’t allowed to talk about, somehow.” (Martha)

MZWANDILE’S STORY

“When I was doing these pictures…because I only took the ones for the parking, front and back…and some people asked me, especially management, if you are taking pictures they will start to say, why are you taking pictures? Where are you going to take them? You know, they are scared you’re going to take them to human rights and all those things that, look, this place is still not what-what for us and all of that. But I said, no, I’m taking these photos for my project. I’m trying to show what you have done for me. You’ve done a lot. You’ve made so many changes within a few months, which means you’ve accepted me from the first day I arrived at this point.” (Mzwandile)

PRIDE’S STORY

“This one is symbolising loneliness. Because I’m still alone now. I don’t have a child. I don’t have a boyfriend. I’m just by myself. I don’t want to be hurt now. I had many disappointments, so now, no, it’s enough. I’ve had enough. That’s why I told myself, no, if God wants me to be like this, then it’s fine. I had dreams as a woman. I also wanted to get married and have children and have my own house. I wanted to be like that, but it never happened. I have my own car and my own house. I only have my house now and the car, that’s all. There’s no one next to me. There’s no shoulder to cry on. You need company at times. But now I don’t want someone who is going to come to take advantage of me at the same time. So I’m very strict when it comes to that. I don’t want people to come and take advantage.” (Pride)

ROSABELLE’S STORY

“In 1977 I attended my first ever South African Championships for Sport for the Disabled. I was at university at the time and a connection to sports was made and established. A whole new world had opened for me. Through Sport I was able to grow as a person, appreciate myself and be in touch with other people who were also physically challenged. My self-image and self-confidence were boosted, especially in my contact with men.” (Rosabelle)

TAZZ’S STORY

“I believe that people with a disability, we still need to look good when you dress up. You need to look good. You need to look neat and present yourself in a clean and neat manner. So for me, I feel as a person with a disability you still need to dress up and look attractive, especially when it comes to women. I still dress up. I still dress up to impress females. When a female sees me I believe that she needs to admire me when she looks at me, not just for being dressed up nicely, but also for my attitude as well. Because people generally have a mindset that people with disabilities are dirty, untidy and they don’t really look good. So they have that kind of mindset that people with disabilities can’t really dress up. When they see I’ve got a nice jacket on they will say, ah, look at this jacket that you have on. So that also helps to change people’s minds, that we still have a sense of style and we still want to look good and be accepted as normal people in society as well.” (Tazz)

VIC’S STORY

“This is images of my wife pregnant and me with my eldest son. I talk about being disabled and my journey and I share personal experiences to my students in terms of what inclusion is all about. I ask them: “What is inclusion all about? You guys are students, when you go out and meet other people, what are their first questions you ask each other?” It doesn’t take very long before they say, well, “who are you?”; “Are you in a relationship?”; you know, “Are you on FaceBook, in a relationship, and what do you do?” And I say, those are the questions that everyone asks. That is what people want to know about you straightaway – what do you do and are you a relationship. That is your identity and value in society. And then I say, “What do you think people ask me when they meet me?” And they get it straightaway – they reply, “What happened to you?” And I say: “Exactly, and that is what sucks about being disabled. People don’t expect me to be in a relationship or be able to do anything because I’m in a wheelchair and so I have less value in society. So, these photographs are about inclusion. This is part of my life; I have some family photos on my bedroom mirror. So this is a direct identity statement about being married, having kids, despite being disabled. I am a husband and a father first, that is my identity and how I see myself – my disability is secondary.” (Vic)